Ukraine

Our last update was released days after the invasion of Ukraine began. At present the Ukrainians are proving to be a tougher and more intractable foe than Putin expected. We still don’t know the outcome of this, but we do know that exports of natural resources, industrial metals, and agricultural goods from both countries will cease for the foreseeable future. This is having obvious results; oil and wheat prices, but also some not so obvious ones. Like Neon. Sure, we can get by without replacing a few fluro tubes, but Neon is actually a crucial input to making semi-conductors (computer chips) and one factory in Odessa supplies 65% of the worlds Neon according to Quartz magazine. If you thought that the COVID-19 disruptions were bad, wait until chip manufacturers deplete Neon stockpiles, and 65% of the market is offline. Inflation will be more ‘sticky’ than expected.

Exchange Shenanigans

Other near misses are occurring that can have a contagion effect on creditworthiness of Systemically Important Financial Institutions. Some have garnered a bit of media attention, but the behind-the-scenes machinations have not had the same exposure. Last week the London Metals Exchange (LME) suspended its Nickel trading operations. The reason was that the price was going vertical. Chinese billionaire Xiang Guangda was short 100,000 tonnes and was reportedly in the hole by $8 billion.

Mr Xiang is no average punter, he is the chairman of Tsingshan Holdings, the number one nickel producer in the world. So maybe it made sense for him to be forward selling some contracts, to lock in the very profitable prices. However, he was way over his skis when nickel started going vertical. In December, nickel was $20,000 a tonne. By late February, with the Russian’s storming into Ukraine, it was up to $24,000 a tonne. On 1 March, it started jumping 6% a day. Then on Monday the 7th, nickel jumped from $29,800 to $42,000. When you are short 100,000 tonnes, that day alone represented a loss of $1.22 billion. It was to get worse. Nickel hit $100,000 a tonne on 8 March. Mr Xiang Guangda was bust. He couldn’t pay the margin call, and said he didn’t want to liquidate!

Here is where the politics gets interesting. The LME is owned by the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing group. They are a public company, but the largest shareholder is the Hong Kong government, with the ability to appoint 6 out of the thirteen directors. The LME decided not only to halt trading to allow a return to an ‘orderly market’, but also decided to cancel all trades that took place above $50,000. Mr Xiang (aka Big Shot) is also reportedly a client of JP Morgan. As chairman of China’s largest nickel producer you can also bet he has friends in very influential political circles.

Was the cancellation of trades solely to help Mr Xiang, or was it also to shield JP Morgan from the fall out if the clients were forced to settle? Who knows, but it smacks of cronyism and politics in the boardroom. The fiasco also had a spill over down here in Australia where Nickel Mines Ltd (NIC) is listed. That company counts Tsingshan as one of its shareholders. Fears were that Tsingshan might dump its shares in NIC to cover the margin call in the nickel position of Mr Xiang. NIC opened on 8 March at $1.75 per share, up 6% on the previous day close, but as news of the great nickel margin call hit, NIC slumped to $1.48, and the next day hit a low of $1.14.

The lesson to be learned is that events far away can have sudden un-expected consequences for third parties.

Sharemarkets

In January we posted an update in the middle of a savage 3 week market sell off advising that a low was possibly near at hand. Within days the markets did indeed bottom. In February, the Australian market had a 3.00% sell off on the day of the Ukraine invasion. On that day we sent an email titled ‘buy on the cannons and sell on the trumpets’. In spite of the horrors we have seen in Ukraine since then, the Australian market is still above the closing price on the first day of the war. The US market however is about 1.9% below the level of 24 February. Australia has no doubt been helped by our exposure to materials, energy and gold.

An update on market results since the start of January:

Nasdaq 100 -19.24%

S&P 500 -12.07%

ASX200 -5.72%

Last month I spoke about the rotation from Growth Stocks to Value stocks. In the US market, Value has outperformed the S&P500 by 6.73% since 1 January, while the Growth factor has underperformed by 7.20%. This rotation back to Value has longer to run, though it will likely be punctuated by short covering rallies.

A similar thing is happening in Australia. A Value factor ETF that I like is the Betashares QOZ. It is down 1.40% while the Vanguard VAS (broad market cap weighted) is down by 5.82% since 1 January.

While markets did rally after those initial shots in Ukraine, there remains a strong chance that we will see markets go lower yet. My thinking is that the S&P 500 could get down to the 3,800 level which is around 20% below the high late last year. The Fed hiking rates as soon as Wednesday will certainly be a test. Consensus is that the Fed will do a 0.25% hike at every meeting for the rest of this year. If that were the case, then ‘buy the dip’ might start to wear a bit thin with people, and we could see some capitulation.

Fixed interest – This time is different!

While we expect equities to be volatile, over the last 40 years bonds have provided a wonderful tail wind and usually gave positive returns in times of stress.

Can we expect that in the future?

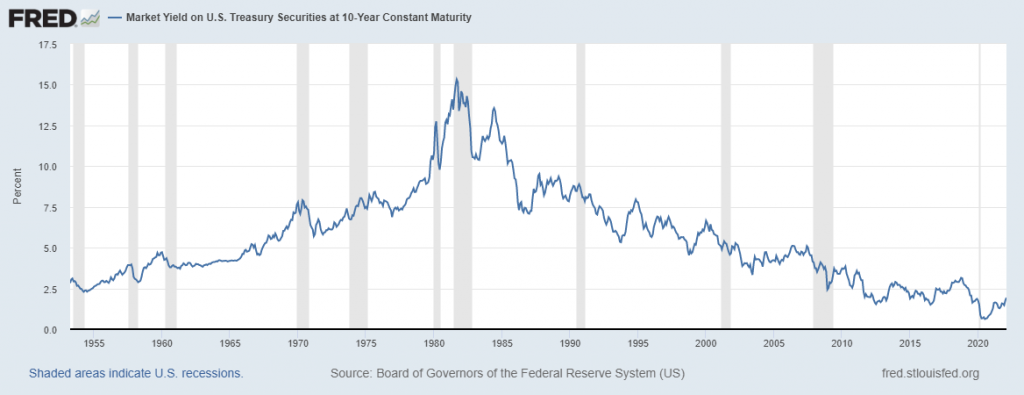

The chart above from the St Louis Fed shows ten-year bond rates over the last 59 years.

It was during the period from 1982 till December 2020 that the 60/40 portfolio reigned supreme. When you ran into a recession, bonds carried a high enough yield that the carry and capital gain as interest rates fell was enough to offset some of the fall in your shares.

The US CPI index is now 7.9% higher than this time last year. Ten year interest rates were 1.99% on the day that was announced. Yes, real rates are negative by 5.91%.

Everyone in the dollar bloc is waiting for the interest rate cycle to commence. Except the Canadians, and the Kiwi’s. Both of those banks have already started hiking rates. We are about to see the first US Fed rate hike since December 2018.

What will the impact be?

Hiking into a Slowdown

The real concern is that the Federal Reserve is ‘hiking into a slowdown’. Usually, the economy is humming along well when the Fed starts to jack up interest rates to cool things down.

Although the economy has heated up and it is hard to find labor, the recovery appears fragile. Consumer confidence surveys and PMI indexes are rolling over.

The dour outlook is seen in the ‘spread’ between 2 year bond rates and the 10 year bond rates. The former yield is 1.74%, while the latter is 1.99%. The spread is a miniscule 0.25%.

Never before has the 2’s/10’s spread been this low just prior to a Fed rate hiking cycle. If the spread turns negative, that is almost a certain recession indicator.

In a recession, credit spreads widen and that means the market price of non-government securities goes down as new investors demand a higher yield to compensate for the additional risk.

If there is no recession the economy holds up or accelerates, then bond yields go up, and that means the price of fixed rate bonds with a long time to maturity go down in price. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t!

So what are the main choices in Fixed Income?

Most Secure – Government Bonds

A portfolio of Australian Government bonds can be bought with one trade, the Vanguard Australian Bond ETF, code is VGB. What do you get? The yield to maturity is 1.63%. The return over the 12 months to 11 March was -3.59%. Yes, government bonds can make a negative return, and that is because market interest rates have risen over the last year. But if you are expecting a recession, and a peak in interest rates, then something like VGB is a great doomsday investment, or even a trading investment to express a short term view that rates might drop a bit.

Slightly less secure – Corporate Bonds (Investment Grade)

Investment grade corporate bonds are those rated BBB or above. If a bond is downgraded by Standard and Poors to BB+ or lower, then it is out of the ‘investment grade’ universe. (the stuff in that bracket is colloquially referred to as ‘junk bonds’) The yield to maturity of the Vanguard Australian Corporate Fixed Interest ETF, (VACF) is 2.13%, and has an average maturity in the bond portfolio of 4.3 years. An increase in market yields to 3.13% could see this ETF fall by another 4%.

To get a better return than either of these traditional fixed income sectors, investors have to move into non-investment grade; take on some trading risk; or invest into an active fund that does some trading to add to the return.

We mentioned these choices in order to point out the conundrum investors face in the fixed income part of their portfolios.

If interest rates rise then a capital loss can occur even in the highest investment grades where you also have long duration (time to maturity of the underlying bonds).

If rising interest rates cripple the economy then that could mean wider credit spreads, which is a further drag on the mark to market value of corporate bonds. With few good choices at the end of a 40 year regime of falling interest rates, investors need to be willing to explore outside the traditional areas. In a future article we will discuss floating rate, senior secured, non-investment grade bonds. In addition the private credit sector, as well as direct first mortgages where yields can still be up to 5.50% with no mark to market risk.

Thanks for the up date ,very interesting

Bill

Thanks fore you up date Mark , very interesting and a bit hard to know just what to do , I will stay put unless you advise otherwise,

Bill